Are Long Term Bonds a Good Investment Now? (Late November 2024)

Yes, long term bonds are arguably a good investment now. The yield on a 20-year U.S. treasury bond has risen from lows of well under 2% in 2020 to a recent 4.5%. That’s arguably a reasonable return on an asset that is risk-free in nominal dollars if held to maturity. And it’s quite possible that this bond will offer capital gains in the short term.

There three reasons that investors might be attracted to long-term government bonds:

- For the secure and fixed annual interest. (And today’s rates are arguably reasonable although not highly attractive.)

- For potential short term capital gains as interest rates fall. (And that’s possible but by no means assured at this time.)

- For the the interest plus the certainty of the eventual return of capital in nominal dollars .

At this time investors could buy long-term government bonds in the hopes for a short term capital gain and failing that (and there could be a capital loss) the bond could be held for the interest and safe in the knowledge that it will eventually mature at par value. Note that interest income is best suited for non-taxable accounts.

Long-term bonds proved to be excellent investments most years all the way from 1980 to 2019 as interest rates fell steadily. Bonds offered what turned out to be attractive interest plus capital gains. But they were terrible investment in 2020 and 2021 because their yields were then so low and because long-term interest rates subsequently rose causing capital value losses on bond holdings. Now that long-term bond interest yields are higher and generally expected to decline, long term bonds may once again be a good investment.

A long term government bond, even though it will mature at precisely its issue price can be surprisingly volatile over its life.

Consider a 20-year U.S. treasury bond issued at $1000 at today’s 4.5% yield. If interest rates drop to 3.5% after one year, the bond is then worth $1137 for a capital gain of 13.7% and that’s in addition to the 4.5% interest received. But it’s a certainty that over its remaining 19 year life the capital gain will reverse and the bond will mature at $1000. And if interest rates instead rise to 5.5% in the year after the purchase then the bond would be worth only $884 for a temporary capital loss of 11.6%. With this kind of volatility in a fixed income investment that will mature with no capital gain or loss, it can be difficult to interpret the performance of long-term bonds.

Looking at past performance, long-term (20-year) bonds purchased from about 1980 to the year 2000, and held until they ultimately matured at par turned out to be very good to good investments strictly because their interest rate yields turned out to be attractive in relation to subsequent inflation. An investment in an index fund that continuously sells and buys bonds to maintain a 20-year maturity did even better because it was capturing capital gains most years as interest rates continued to decline.

Long-term (20-year) bonds purchased from 2012 to 2019, and which are not yet near maturity, had, as of 2020, provided very good returns in spite of their low yields (under 3% in most cases). Capital gains had greatly boosted their returns. But those capital gains were subsequently wiped out as interest rates recently rose significantly. As of their ultimate maturity those bonds will have provided poor returns strictly because of their low yields at the date of issuance.

The analysis here is based on U.S. data for stocks (S&P 500 index) and bonds (20-year U.S. government treasury bonds) from 1926 through October 2024. The data source is a well-known reference book called “Stocks, Bonds, Bills and Inflation”. The formerly annual reference book has sadly been discontinued. But, as a Chartered Financial Analyst, I have access to the updated data.

Zero-coupon or Strip Bonds

It is important to understand that the return on a long-term zero-coupon government bond that will be held to maturity is precisely known at the purchase date.

To analyze historic bond returns or expected future bond returns it is best to start with the simplest type of bond which is a bond that only pays off at maturity. These are called zero-coupon bonds because there are no annual interest payments. Bond interest is sometimes referred to as coupon payments since bonds used to have detachable physical interest “coupons” attached. Zero-coupon bonds are also known as “strip bonds” because they can be created by “stripping” the interest payments or notional “coupons” from regular bonds. Zero-coupon twenty-year bonds, for example, represent a lump sum to be received in 20 years. The lack of annual interest payments simplifies the analysis. Long-term zero-coupon bonds are purchased at a large discount to their face value and the interest is effectively received all at once when the bond eventually matures at its much higher face value.

From 1980 to 2020, long-term zero-coupon bonds provided excellent returns. A zero-coupon twenty-year U.S. government bond purchased in 1982 and held to maturity in 2002 ultimately returned precisely its initial yield which was about 14%. A zero-coupon twenty-year U.S. government bond purchased in December 2000 and held to maturity in December 2020 returned precisely its initial yield which was about 5.6%.

Regular bonds, in contrast, pay annual annual or semi-annual interest. A regular bond issued in 1982 and paying 14% annually ended up returning something less than 14% over its life since the annual interest payments (of $140 per $1000 bond) would have been reinvested each year at prevailing interest rates that turned out to be below 14%.

A new zero-coupon twenty-year U.S. government bond purchased today and held to its maturity in November 2044 will return precisely its initial yield which is currently about 4.5%. A regular 20-year bond paying annual interest will return something different than a 4.5% yield over its life depending on the future interest rates that the annual interest payments can be re-invested at.

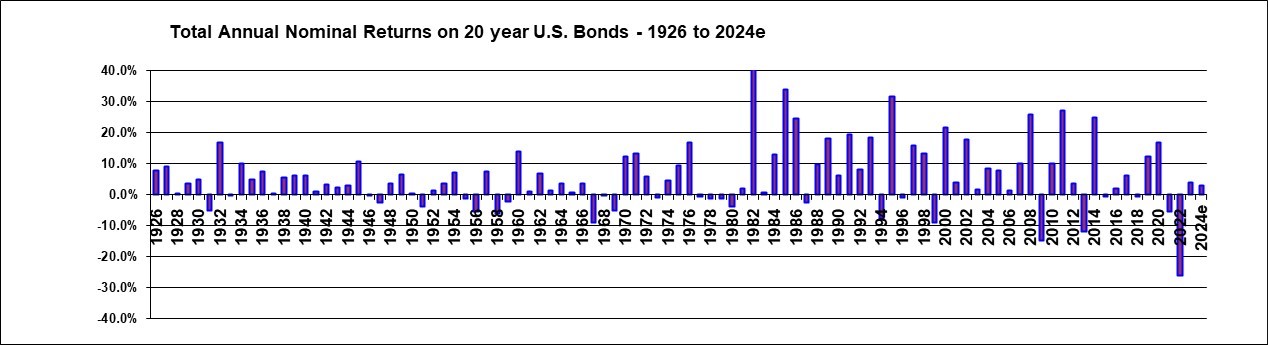

Historic one-year annual return of long-term bonds.

Despite the fact that they will mature at par, long-term bonds returns on an annual basis are quite volatile due to their temporary capital gains and losses as interest rates change over the life of a bond.

The above chart shows the return on a new 20-year zero-coupon bond purchased at the start of each year. Returns were very high in many of the years from 1982 to 2020 as interest rates fell most years. In 2022 there was a significant loss on such a bond as interest rates rose sharply.

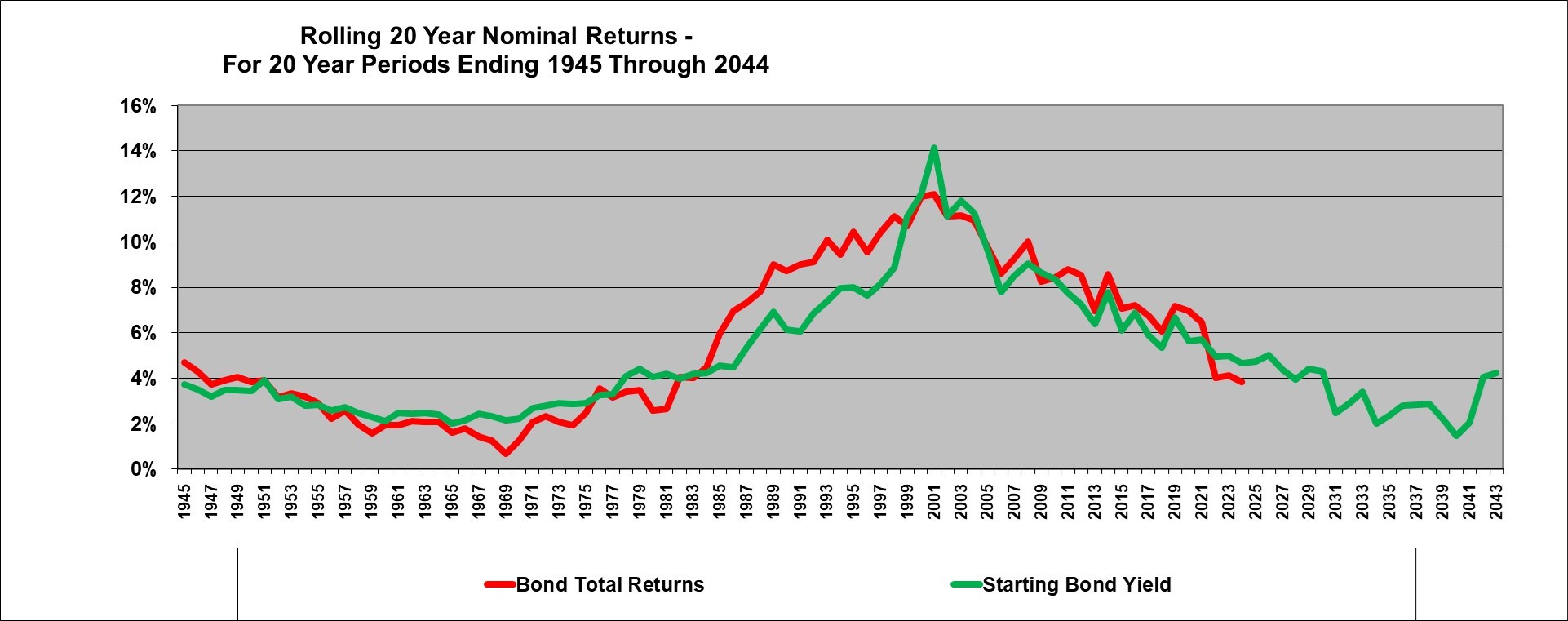

Historic results for all 20 calendar year holding periods

The following graph shows the rolling 20-year returns from a 20-year bond index fund for all 20 (calendar) year periods ending 1945 through 2024 – note that 2024 uses data through October. (So a series of 20-year periods beginning at the start of each year from 1926 through 2005.) Note that a 20-year bond index fund would sell the bonds annually (for a capital gain or loss) and reinvest in new 20 year bonds in order to maintain a constant approximate 20 year maturity. The graph also includes what the 20-year bond interest rate was at the start of those periods. We also already know the interest rate at the start of the 20 year periods that will end in 2025 through 2044. And we graph that because the returns from the bond index are likely to track that beginning interest rate fairly closely.

To interpret this graph, we can start from the left side. An investment in a 20-year U.S. government bond index at the start of 1926 and held until the of 1945 provided a compounded return of 4.7% over the 20 years.

Prospective long -term bond investors should be aware of the low bond returns for all the 20 year periods stated in the 1940’s and ended in the 1960’s.

In the 20 year periods that ended in 2001 through 2020, investing in a 20-year U.S. bond index fund would have provided a return that was very similar to and occasionally higher than the return from stocks over the same 20 years.

It seems quite likely that when the returns from holding stocks for 20 years starting at the beginning of all the years from 2002 through to 2022 (and ending 2021 through 2041) are ultimately known, we will likely see the return from the 20-year bond index fund track down because the starting bond yields were so much lower. And then for 20-year bond investments started at the beginning of 2023 or 2024 and ending 2042 and 2043, we will see the bond returns recover to above 4%.

Why did 20-year long-term government bonds provide unexpectedly good returns for most investment periods starting since about 1982?

Several years ago investors were pointing out that a long term investment in U.S. treasury bonds had provided returns similar to the S&P 500 for 20 -year periods ending 2001 to 2020 and at far less risk. However that was a situation that was destined to end.

Long-term government bonds can provide good returns for two possible reasons. But one of the reasons is always only temporary.

The first and most important reason why a long term bond may provide a good return is that the initial interest rate paid by the bond turns out to be an attractive rate over the life of the bond.

20-year U.S. bonds issued in 1982 at 14% provided an excellent return (of precisely 14% annually for zero-coupon bonds and about 11% for regular bonds due to the reinvestment of annual interest payments at lower interest rates) if held through to their maturity in 2002 solely because that 14% was, in retrospect, a good return. Had we had hyper-inflation (as some feared at the time) then 14% might not have been a poor return. But the 1982 (zero-coupon) bond provided a 14% return simply because that was what it paid. And we now know, in retrospect, that this was a good return over the 20 years from 1982 to 2002.

The second but temporary reason that bonds can provide a good return also came (temporarily) into play for the 1982 bond.

In 1983 the market interest rate on 20-year government bonds dropped to about 11% (from 14% in 1982). This provided a significant (23%!) but temporary boost in the market value of the 1982 bond. The 1982 bond would have traded at a premium over much of its life as long-term interest rates declined significantly over the years. But in 2002 the bond matured at exactly its par value. The capital gain on the value of the 1982 bond was temporary and eventually the bond value declined to precisely its initial par value.

Over its full life the 14% return on the 14% 1982 zero coupon government bond was entirely driven by its contractual 14% interest rate. The decline in interest rates initially boosted its value but that was only a temporary impact. The fact that interest rates on 20-year bonds in 2002 had declined to 5.9% had no impact at all on the ultimate return at maturity in 2002 provided by the 1982 bond.

The situation for a 20-year bond index fund that continually sells bonds annually and buys new 20 year bonds to maintain a constant maturity of approximately 20 years is somewhat different. The capital gain in a falling rate environment would persist until some time after rates reversed and moved higher.

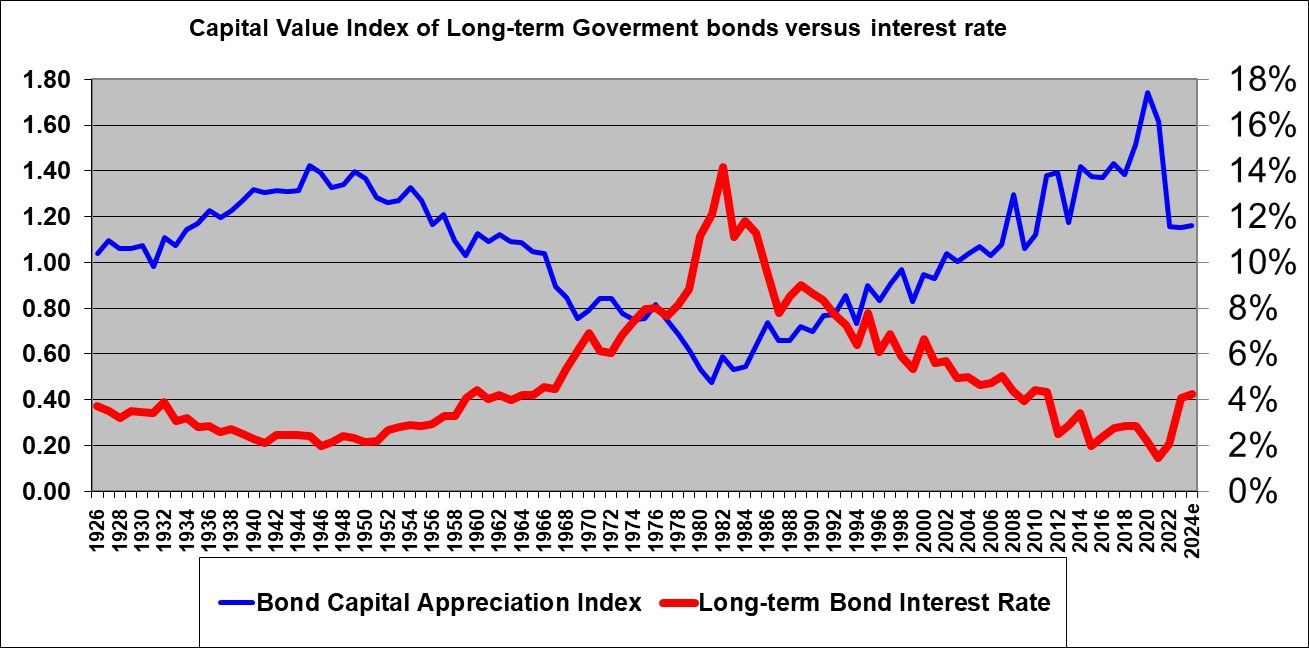

Bond Temporary Capital Appreciation

The temporary nature of market value gains on long-term government bonds is illustrated in the next graph which shows an index of the capital appreciation value of a 20-year government bonds index fund since 1926.

The blue line, plotted on the left scale, shows the capital appreciation on an index of 20-year U.S. government bonds starting at 1.00 at the start of 1926. The index had risen slightly above 1.0 by the end of 1926, the first point on the graph. The index then rose significantly to 1.40 in the mid 1940’s. This meant that an investment permanently maintained in 20 year government bonds through annual rollovers to new 20 year bonds and originally made in 1926 had appreciated in capital value by 40%. This excludes the value of the annual interest payments. This 40% is significant but keep in mind that it was built up over 20 years and therefore amounted to an average compounded amount of 1.7% per year.

This 40% capital value increase was driven by long-term interest rates (shown on the red line plotted on the right scale) dropping from 4% at the start of 1926 down to 2.0% in the mid 1940’s. But this capital appreciation value gain eventually evaporated as the index returned to 1.0 when interest rates returned to 4% around 1959. And the bond capital value index slumped to about 0.50 in 1982 as long-term interest rates rose to 14%. This meant that the capital portion (which totally excludes the interest payments) of an investment in long-term government bonds made in 1926 (or at anytime the capital value line was at 1.0) was worth only about 50% of the initial invested amount! The index then rose steadily all the way back to (not coincidently) about 1.40 as interest rates recently declined all the way back close to about the the 2% level of 1926 and the mid 1940’s. And the index has peaked at about 1.75 at the end of 2020 as the interest rate on a 20-year bond fell below 2.0% and a record low. The Capital appreciation index then plummeted as interest rates rose sharply in 2022 but the index remains above 1.0.

The red line, plotted on the right scale also shows the initial interest rate which is also the return that would have been made by those investing in and holding to maturity a 20-year zero coupon bond in each year from 1926 to 2020. An investor in 1932 would have made 4%. An investor in the 1940’s would have made barely over 2%, An investor at the peak in the early 80’s would have made 14% and today’s (November 28, 2024) investor in a 20-year zero coupon U.S. government bond held to maturity will, of a certainty, make a compounded annual return of 4.5% to maturity in 2044. Regular bonds are not zero coupon and therefore investors in regular bonds would have experienced somewhat different returns by reinvesting the annual interest payments. And investors in a 20-year bond index fund make a return generally quite similar to the starting interest rate as illustrated in other graphs further above.

What Return can we now expect from 20-year bonds?

A 20-year U.S. zero-coupon government bond purchased today should be expected, over its full life, to return its current yield of about 4.5% per year. If 20-year interest rates soon decline then the bond will provide a temporary gain in market value. If interest rates increase it will suffer a temporary loss in market value. But over its life this bond will return only and precisely its promised yield to maturity of 4.5%.

Should we invest in long-term government bonds?

The data appears to suggest that the answer is no. Not unless you are satisfied with an expected return on the order of 1.8% for 20-year government bonds. And long-term higher rated corporate bonds also will return no more than about 2.8% if held to maturity, since that is their approximate current yield. However, if you wish to speculate and bet that interest rates will fall then in that case a 20-year bond could be used to make that speculative bet. In that case you would be planning or hoping to sell the bond for a capital gain in the relatively short term.

END

Shawn Allen, President

InvestorsFriend Inc.

November 28, 2024

The original version of this article was written in 2012 when 20-year U.S. bond interest rates were 2.4%. As of today following the advice of that article to avoid long-term bonds at that time would have worked out well. And an update in February 2021 when the yield was 1.8% was correct in saying to avoid long-term bonds at that time.