Click for updated version of this article

Are Long Term Bonds a Good Investment in 2012?

In this article I show data which I believe indicates that long-term bonds are an exceedingly poor investment at this time. The data appears to indicate that long-term bonds are an investment to be avoided with extreme prejudice. That long-term bonds do not have any place in an investment portfolio at this time.

This is in spite of the fact that long-term bonds have been a very good investment since 1980.

The analysis here looks at the option of investing in (or continuing to hold) long-term bonds versus stocks for long-term investments at this time. For long-term we focus on 20 years. This analysis does not look at or comment on short-term investments where in fact short-term bonds may be a viable option. This analysis also does not consider the option of delaying long term investments by staying with or moving to cash or short-term investments. It focuses on whether holding or buying long-term bonds at this time is a good investment and makes some comparisons to the long-term returns expected from stocks.

The analysis here is based on U.S. data for stocks (S&P 500 index) and bonds (20-year treasuries) from 1926 through 2011. The data source is a well-known reference book called “Stocks, Bonds, Bills and Inflation” 2012 edition. The book is published annually by Morningstar. (Ibbotson SBBI classic yearbook).

A truthful but most dangerous observation…

One of the most dangerous observations currently being made is that long-term bonds have outperformed stocks over the past year, the past five years, the past 10 years, the past 20 years and even the past 30 years.

It’s a true observation. But it is a highly dangerous observation because it implies that long-term bonds are likely to be a better investment than stocks going forward.

In fact, long-term bonds purchased today are almost guaranteed to under-perform stocks over the next 20 years.

The return on a long-term bond is known at the purchase date

To analyze historic bond returns or expected future bond returns it is best to start with the simplest type of bond which is a bond which only pays off at maturity. These are called zero-coupon bonds because there are no interest (and bond interest is sometimes referred to as coupon payments, because bonds used to have interest coupons attached). Zero-coupon twenty year bonds, for example, represent a lump sum to be received in 20 years. The lack of annual interest payments simplifies the analysis.

A zero-coupon twenty year U.S. government bond purchased in 1982 and held to maturity in 2002 returned precisely it’s initial yield which was about 13.5%. A zero-coupon twenty year U.S. government bond purchased in 1992 and held to maturity in 2012 returned precisely it’s initial yield which was 7.26%.

Regular bonds, in contrast, pay annual interest. A regular bond issued in 1982 and paying 13.5% annually ended up returning something less than 13.5% over its life since the annual interest payments would have been reinvested at prevailing interest rates below 13.5%.

A zero-coupon twenty-year U.S. government bond purchased today and held to its maturity in 2032 will return precisely its initial yield which is just 2.4%. A regular 20-year bond paying annual interest will also return something very close to 2.4% over its life. This is because the 2.4% annual interest payments are so small that it won’t matter much what interest rate those annual interest payments are reinvested at.

It seems obvious that 2.4% is not a good return. And there are also very good reasons to think that stocks will return quite a bit more than 2.4% annually over the next twenty years. More about that below.

Bonds have indeed beaten stocks over the past 30 years

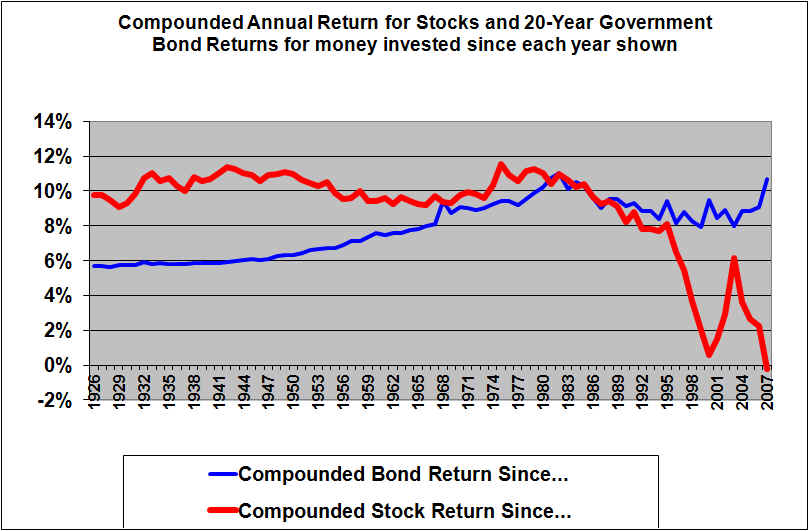

The following graph shows the compounded annual returns from investing in 20-year U.S. government bonds versus the investing in the S&P 500 index. The annual compounded returns for purchasing at each historic date and holding until the end of 2011 are shown.

To interpret this graph, let’s start with the right hand end of scale at 2007 and then move left. The red line shows that a lump-sum investment in stocks made in 2007 returned a compounded annual amount of about zero percent through the end of 2011, while the blue line shows that an investment in 20-year U.S. government bonds returned a compounded amount of over 10% annually as at the end of 2011.

Moving left we can see that these long-term bonds have turned out to be by far the superior investment for lump sum (as opposed to annual investments) money invested each year all the way back to about 1997. (The blue bonds line is higher than the red stocks line.) And bonds have turned out (as at the end of 2011) to deliver moderately better results for investments made in the years 1987 through 1996. And prior to that an investment in these bonds in the years 1980 to 1986 and held and reinvested through the end of 2011, provided a return about equal to that from stocks.

During the 1970’s however, history now reveals that buying stocks and holding through to the end of 2011 was a better investment than going with and staying with 20-year bonds, although not by a huge amount.

A permanent investment in 20-year bonds all the way back in 1968 turned out to provide an equal return to that from stocks in the next 43 years through to the end of 2011. But 1968 was an anomalous year, other than 1968 in all years shown prior to 1980, it was better to be in the stock index than the 20-year government bond index from that year until the end of 2011.

Permanent investments in stocks prior to 1968 have turned out to provide a higher return, as at the end of 2011, than a permanent investment in 20-year bonds and by quite a large margin.

Why did long-term government bonds provide good returns in the past three decades or more?

Long-term government bonds can provide good returns for two possible reasons. But one of the reasons is only temporary.

The first and most important reasons why a long bond may provide a good return is that the initial interest rate paid by the bond turns out to be an attractive rate over the life of the bond.

20-year U.S. bonds issued in 1982 at 13.5% provided an excellent return (of precisely 13.5% annually for zero-coupon bonds and about 10.2% for regular bonds due to the reinvestment of annual interest payments at lower interest rates) through maturity in 2002 because that 13.5% was in retrospect a good return. Had we had hyper-inflation (as some feared at the time) then 13.5% might sound like a poor return. But the 1982 (zero-coupon) bond provided a 13.5% return simply because that was what it paid. And we know, in retrospect, that this was a good return over the 20 years from 1982 to 2002.

The second but temporary reason that bonds can provide a good return also came (temporarily) into play for the 1982 bond.

In 1983 the market interest rate on 20-year government bonds dropped to 10.4% (from 13.5% in 1982). This provided a significant but temporary boost in the market value of the 1982 bond. The 1982 bond would have traded at a premium over much of its life as interest rates dropped all the way to 5.4% in 2002. But in 2002 the bond matured at exactly its par value. The capital gain on the value of the 1982 bond was temporary and eventually the bond value declined to precisely its initial par value.

Over its full life the 13.5% return on the 13.5% 1982 zero coupon government bond was entirely driven by its contractual 13.5% interest rate. The decline in interest rates initially boosted its value but that was only a temporary impact.

The temporary nature of market value gains on long-term government bonds is illustrated in the next graph which shows an index of the capital appreciation on 20-year government bonds since 1926.

The blue line, plotted on the left scale, shows an index of capital appreciation on 20-year government bonds starting at 1.00 at the start of 1926. The index rose slightly byt the end of 1926. The index rose significantly to 1.40 in the 1940’s. This was driven by interest rates (shown on the red line plotted on the right scale) dropping from 4% in 1926 down to 2.0% in the 1940’s. But this capital appreciation gain eventually evaporated as the index returned to 1.0 when interest rates returned to 4% around 1959. And the index slumped to about 0.50 in 1982 as long-term interest rates rose to 13.5%. The index then rose steadily all the way back to (not coincidently) about 1.40 as interest declined all the way back close to the 2% level of the 1940’s.

Consider the long-bond issued at the end of 2010 and its misleading recent return…

An investment in the 20-year government bond index at the end of 2010 returned a remarkable 28% in 2011. This was due to an equally remarkable decline in the market interest rate on these bonds from 4.13% to 2.57% during 2011.

Ultimately however, that end of 2010 (zero-coupon) government bond is going to return precisely 4.13% compounded per year over its 20 year life. The Capital gain due to an interest rate decline in 2011 provides only a temporary gain that will be reversed. The 28% gain is largely irrelevant to long-term bond holders. It is only relevant to bond traders that have sold or will sell the bond prior to the capital gain reversing.

What Return can we now expect from 20-year bonds?

A 20-year U.S. government bond purchased today should be expected to return its yield of 2.4% per year. If interest rates decline further it may provide a temporary gain in market value. If interest rates increase it will suffer a temporary loss in market value. But over its life this bond will return only 2.4%.

The fact that an investment in 20-year bonds made at any time over the past 40 years has returned a compounded 8% or more is completely irrelevant. Some of that return will prove to have been temporary as bonds valued at well above par eventually mature at only par value. Far from recurring in future, this temporary return boost is almost certain to reverse in future years. Much of the 8% or more return has occurred simply because bond interest rates, over the past few decades, were much higher than today.

It would be quite unrealistic to assume that a twenty-year 2.4% bond issued today will ultimately earn (over its full life) anything close to the 8.2% return offered by bonds issued in 1991. If you base your bond return expectation on the average bond returns in the past 30 years you will implicitly be making a highly unrealistic assumption.

Technically, the return from a 2012 20-year bond will be a little bit different than precisely the 2.4% initial yield if interest rates change. If interest rates rise there will be an opportunity to reinvest the annual interest payments at a higher rate. Or, if interest rates decline the reinvestment will be at lower rates which would lower the 2.4% return. However with the annual interest coupons on a $1000 bond being a meager $24, the impact of reinvested interest is minor at today’s low interest rates.

Is a 3% return really that much worse than a 6% return?

Over 30 years $1000 invested at 3% grows to $2,427. (Not so bad perhaps, until one considers inflation and income taxes). $1000 invested for 30 years at 6% grows to $5,473. That’s 2.25 times as much when the interest rate doubled. The extra 0.25 comes from compounding though the impact of compounding is weak at 6% interest rates.

Perhaps making 2% is really not that much worse than making 3%, both are pathetic even before inflation and taxes and absolutely abysmal after inflation and taxes.

At 9% our $1000 would grow to $13,268 or 5.47 times more when the interest rate tripled (the impacts of compounding are starting to be noticeable).

At the 12% interest rates that were available in the early 1980’s (due to forecasts of continued double digit inflation which then faded away) our $1000 grows to $29,960. This is 12.34 times larger when the interest rate went up by 4 times from 3% to 12%. In this case the impacts of compounding are very significant indeed.

The conclusion here is that few more points of return are very significant over 30 years once you get above 6% or so and increasingly significant at higher return rates. But at very low interest rates like 3% the difference of a point of return is not that big a detail (since a bit more than nearly nothing is still not much).

Should we invest in long-term bonds?

In my view the data indicates that the answer is a resounding “NO!”. Not unless you are satisfied with an expected return on the order of 2.4% for 20-year government bonds. And long-term higher rated corporate bonds also will return no more than about 3.7% to 4.0% if held to maturity, since that is their approximate current yields.

Why should we expect Stocks to Return more than bonds?

The wrong way to predict stock returns would be to look at the return since year 2000 of about zero percent or to look at the long term historical return of about 10% per year.

Mathematically the return from stocks will equal the dividend yield plus the rate of growth in dividends. (This assumes the P/E ratio will remain constant. Since the current P/E ratios are moderately below historical averages, it seems reasonable to assume that there is not much risk of a long-term permanent decline in the P/E ratios). The dividend yield on the S&P 500 is currently 2.2%. If earnings per share grow at about the rate of GDP, say 2% real plus 2% for inflation, this would suggest that stocks will return about 6.2%. Although this is low, it easily beats the expected return on long-term bonds.

Implications for Investors, Including Pension Funds

Long-term government bonds purchased or held in 2012 are destined to return only about 2.4% over their remaining lives. Corporations, meanwhile are providing dividend yields of 2.2% and the dividends can reasonably be expected to grow at 4% or more for a total return of 6.2% or more over the long term.

I believe that history will show that pension funds and other investors that make large allocations to (or even continue to hold large allocations of) long-term bonds in 2012 are making a serious mistake.

Pension funds and other large institutional investors are blindly following their historic asset allocation percentages and are ignoring common sense. Bond returns have been very good because long-term interest rates have dropped. But that same drop guarantees that bond returns, from a 2012 investment in 20 year bonds will be very low indeed over the next 20 years. And one has to be very pessimistic to forecast that stocks will fail to materially exceed these low bond returns.

Conclusion

Money invested in stocks in 2012 is almost (but never quite) certain to exceed the return from investing in long term government bonds in 2012 which will, of a certainty, be in the range of 2.4%.

In the short term, bonds may continue to do better than stocks. But stocks will almost definitely do better than bonds over the next twenty years.

Warning

The suggestion to avoid long-term bonds at this time violates the traditional advice to always maintain some exposure to long-term bonds in your asset allocation. My belief is that following a traditional asset allocation approach at a time when interest rates are at about the lowest levels in history defies common sense. History will be the judge.

Again, note that this article says nothing about holding cash or short-term bonds, it only compares long-term bonds with stocks.

END

Shawn Allen, President

InvestorsFriend Inc.

August 13, 2012 (with edits to October 21, 2012)

Post Script:

We can turn to Warren Buffett for some support for our arguments above.

In his 1984 letter, Warren Buffett wrote about the irrationality of investors buying long-term bonds at times of very low interest rates.

“Our approach to bond investment – treating it as an unusual sort of “business” with special advantages and disadvantages – may strike you as a bit quirky. However, we believe that many staggering errors by investors could have been avoided if they had viewed bond investment with a businessman’s perspective. For example, in 1946, 20-year AAA tax-exempt bonds traded at slightly below a 1% yield. In effect, the buyer of those bonds at that time bought a “business” that earned about 1% on “book value” (and that, moreover, could never earn a dime more than 1% on book), and paid 100 cents on the dollar for that abominable business.”

“If an investor had been business-minded enough to think in those terms – and that was the precise reality of the bargain struck – he would have laughed at the proposition and walked away. For, at the same time, businesses with excellent future prospects could have been bought at, or close to, book value while earning 10%, 12%, or 15% after tax on book. Probably no business in America changed hands in 1946 at book value that the buyer believed lacked the ability to earn more than 1% on book. But investors with bond-buying habits eagerly made economic commitments throughout the year on just that basis. Similar, although less extreme, conditions prevailed for the next two decades as bond investors happily signed up for twenty or thirty years on terms outrageously inadequate by business standards.”

Final Word

Buffett described buying tax-exempt bonds at yields around 1% in 1946 as in effect the purchase of an abominable business. And he said the bond investors accepted terms that were outrageously inadequate by business standards for the two decades after 1946. I don’t know what tax exempt bonds paid during that period but 20-year government bonds yielded 2.12% in 1946 and rose to 4.55% by 1966. Today, the 20 year yield at 2.4% seems to fit solidly into the range where Buffett considered an investment in long-bonds to be similar to the purchase of an abominable business offering terms that are outrageously inadequate by business standards. And today, the S&P 500 trades at an earnings yield of about 6%, which is vastly higher than the bond cash yield. It is true that the stock earnings yield is not available in cash (although about 2% of it is as dividends). The remaining 4% earnings yield is retained by the companies for reinvestment for the future benefit of the share owners.

It would be a mistake to invest in long-term bonds today on the basis that they have been beating stocks for many years. We know, of a certainty, that long-term bonds purchased today will provide meager returns around 2.4%. And we can rationally expect stock returns (with 2% dividends and another 4% retained for reinvestment, at relatively high ROEs) to be higher, over the next 20 years, than these inadequate bond returns.